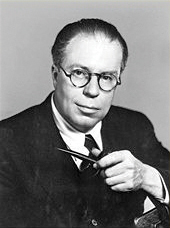

Long Island remembers its men of letters. Christopher Morley (1890-1957), the longtime Roslyn Estates resident who has a park and Knothole Club named for him, is just one example. There are other honors, namely Walt Whitman Road, Walt Whitman High School, even the village of Melville might have been named for the famous New York-born author of Moby Dick. Such efforts remind me of a line in a poem, “Sorrows of Intellectual Life” by Fred Chappell, the former poet laureate of North Carolina:

Long Island remembers its men of letters. Christopher Morley (1890-1957), the longtime Roslyn Estates resident who has a park and Knothole Club named for him, is just one example. There are other honors, namely Walt Whitman Road, Walt Whitman High School, even the village of Melville might have been named for the famous New York-born author of Moby Dick. Such efforts remind me of a line in a poem, “Sorrows of Intellectual Life” by Fred Chappell, the former poet laureate of North Carolina:

Search all of America from coast to coast,

You’ll never find a Boulevard Robert Frost,

No Stevens Stadium, no Eliot Avenue:

The books are many, the monuments are few.

Ginsberg and Roethke could mesmerize the house,

But now lie fodder for silverfish and mouse.

Here in Roslyn, we have not only Morley Park, but also the Bryant Library and the Bryant Viaduct, not to mention the best public libraries in the United States. Let’s hope that young people take advantage of it.

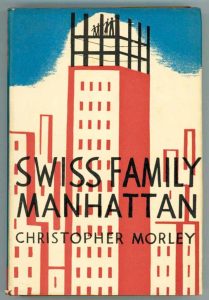

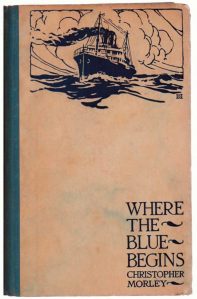

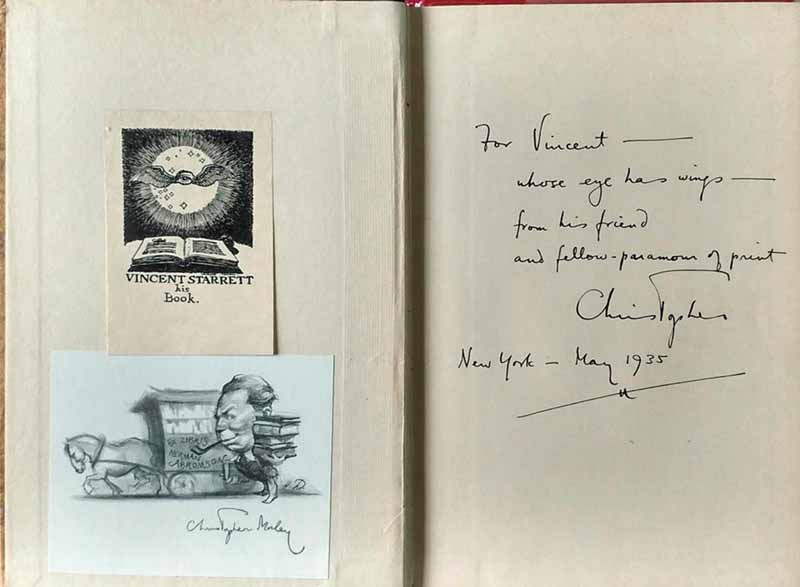

Morley has one fine non-fiction collection in print. Christopher Morley’s New York is a compilation of newspaper columns Morley wrote from the 1920s to the 1950s. Morley was a man of letters. He edited the Saturday

Review of Literature and co-founded the Baker Street Irregulars, a literary society dedicated to the study of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories. He also served as an editor for the Book-Of-The Month Club. Following in the footsteps of William Cullen Bryant, Morley achieved fame as a columnist for The New York Evening Post.

That he wrote for newspapers was common in that era: Edgar Allan Poe, Walt Whitman, Mark Twain and Ernest Hemingway all worked as journalists. By the time of World War II, this was changing. In time, universities, not the newspaper office, is where the writer would find sanctuary. Newspapers, in Morley’s day, were not necessarily journalism. The old America had political wars, but not so much the culture wars of today. Newspapers were also literary: Dense and numerous book reviews, poetry on page one. Not all of it was florid, either. Take 1955. Game One of the World Series between the Yankees and the Brooklyn Dodgers. Marianne Moore, the famed poet and Brooklyn Dodger fan, who lived in Fort Greene, wrote a poem in honor of her beloved Bums, one that appeared on page one of The New York Daily News, then enjoying a circulation north of 2 million. Two decades earlier, in 1936, Moore’s fellow modernist poet, Allen Tate, wrote his lyrical “To The Lacemonians” for page one of The Richmond News, verse honoring a Confederate soldiers reunion. Think about it. Cutting-edge poetry right there on page one.

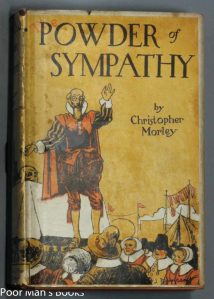

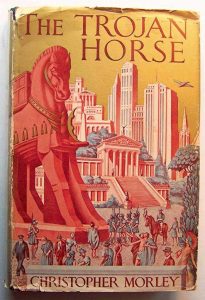

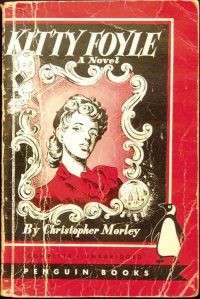

Morley, too, wrote poetry, even though he was not identified with any school of verse. He was, to be sure, a promethean man of letters, publishing such well-received novels as Parnassus on Wheels, The Haunted Bookshop and Kitty Foyle, the latter of which was made into an Academy Award-winning movie. Above all, Morley was a prose poet of New York. He loved the city, searching out and celebrating any atom of it. What Dr. Johnson famously said about 19th century London was true of Morley’s early-20th century New York: Tired of it and you are tired of life.

Morley was lucky to have lived when he did. New York was a financial and cultural capital. But it was not a political capital. It was a safe city, whose public schools produced Nobel Prize winners. In his novel, Closing Time, Joseph Heller recalled radio broadcasts signing off by saluting the city as one where “seven million people lived in peaceful democracy.” In Morley’s day, the number was about five million. What did Morley love about New York?

Like Alfred Kazin, he was a walker in the city. He loved the world of books and bookstores, of museums, of music halls, a city where one could constantly pursue the life of the mind. He loved, too, the world of tugboats and subways. Morley was a lifelong gourmet; he loved the city of restaurants and saloons. Morley championed the era of three-hour lunches, when men could dine and drink and talk. A graduate of Oxford University and a lifelong Anglophile, Morley gravitated towards the world of clubs and male bonding.

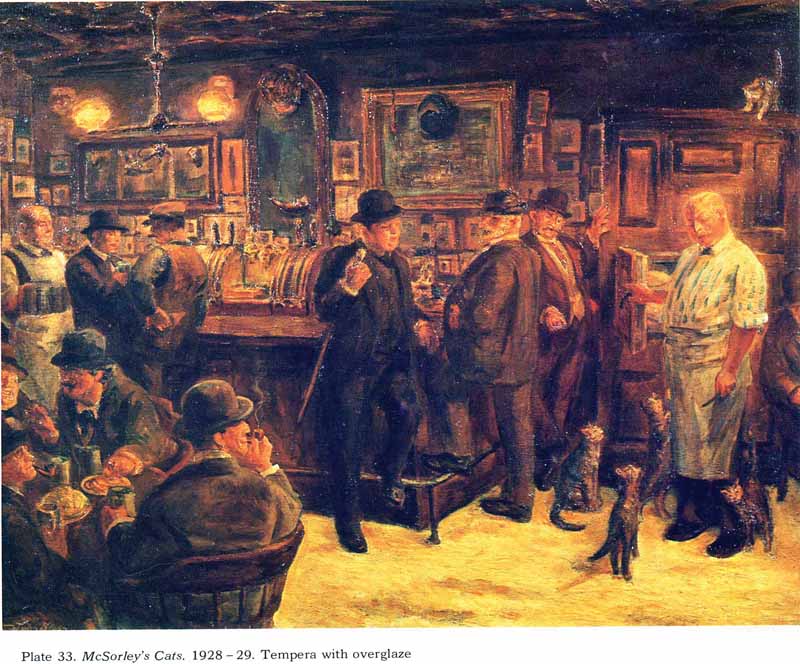

Not surprisingly, all roads headed to McSorley’s wonderful saloon in the Lower East Side, where a Christopher Morley could sit and eat and drink and most importantly, write and edit in peace for hours on end. Morley, like other poets of his day, was especially entranced by the Woolworth Building, the city’s first great skyscraper, a building that dominated New York until the era of the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building took over. Morley also loved West End Avenue, a boulevard that he praised for being “fresh with life” and full of adventure.

It is noteworthy also that Morley was not a native. He grew up in Haverhill, PA, and like countless other ambitious young people, then and now, he made a beeline to the big city. Think O. Henry, Hart Crane, Thomas Wolfe, Tom Wolfe and Jay McInerney, among many others, out-of-towners who also sang of the great city. Morley occasionally cast a cold eye on New York. In one column, he particularly mourned the passing of a nymph statue, a Diana model, claiming that something beautiful had been gutted from New York. We all have our stories to tell on this front. He sympathized with the struggles of the commuter.

He noted the advances of modernity encroaching on his beloved and then-rustic Roslyn, while eventually coming to terms with the amenities of suburban life. Morley’s life mirrored the history of twentieth-century New York: When the pre-World War II New York disappeared, people learned that the prosperity of 1950s suburbia was a good enough trade-off.

He noted the advances of modernity encroaching on his beloved and then-rustic Roslyn, while eventually coming to terms with the amenities of suburban life. Morley’s life mirrored the history of twentieth-century New York: When the pre-World War II New York disappeared, people learned that the prosperity of 1950s suburbia was a good enough trade-off.

Morley was an innocent in New York. His New York was the capital city of that rough-and-tumble nation that lived from the end of World War I until Dec. 7, 1941. What New Yorkers worried about in the post-World War II-era—crime, public schools, a rising cost of living—never entered his mind, at least in what he wrote. Morley was a man who was lucky to have lived when he did.